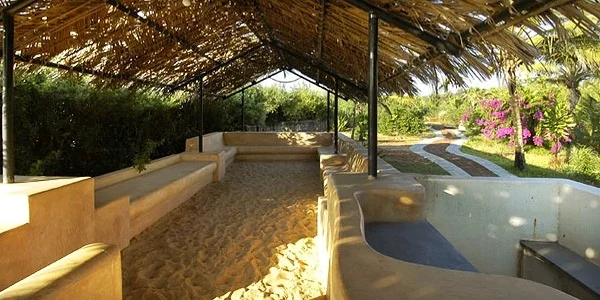

In this Q&A session, I take up a material that we frequently use in our houses in Goa - Indian Patent Stone or IPS. The material is incredibly versatile as it comes in a wide range of colours and is suitable for a number of surfaces right from floors to walls to counters to inbuilt furniture such as the balcao. Over the session I also answer questions about how the material ages with cracks and address the important precautions that need to be taken while using the seamless material. We discuss the similarities between IPS and oxide floors and how the material application technique has involved. We also speak about the curing and workmanship that is required to achieve the best finish.

Tune in to watch the entire session.

Featured

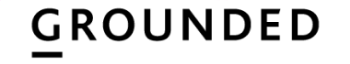

Terracota figures atop Goan roofs

Architecture, A Grounded Palette, House for Sale in GoaRoshini GaneshArchitecture, architecture india, IPS, Oxide Finish, Indian Patent Stone, construction materials, House for Sale Goa, house in goa for sale, houses in goa for sale, House for sale in Goa, home in goa, Contemporary interiors, Maintenance of vacation home, real estate goa, Lime, Plaster, seamless finishComment