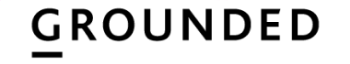

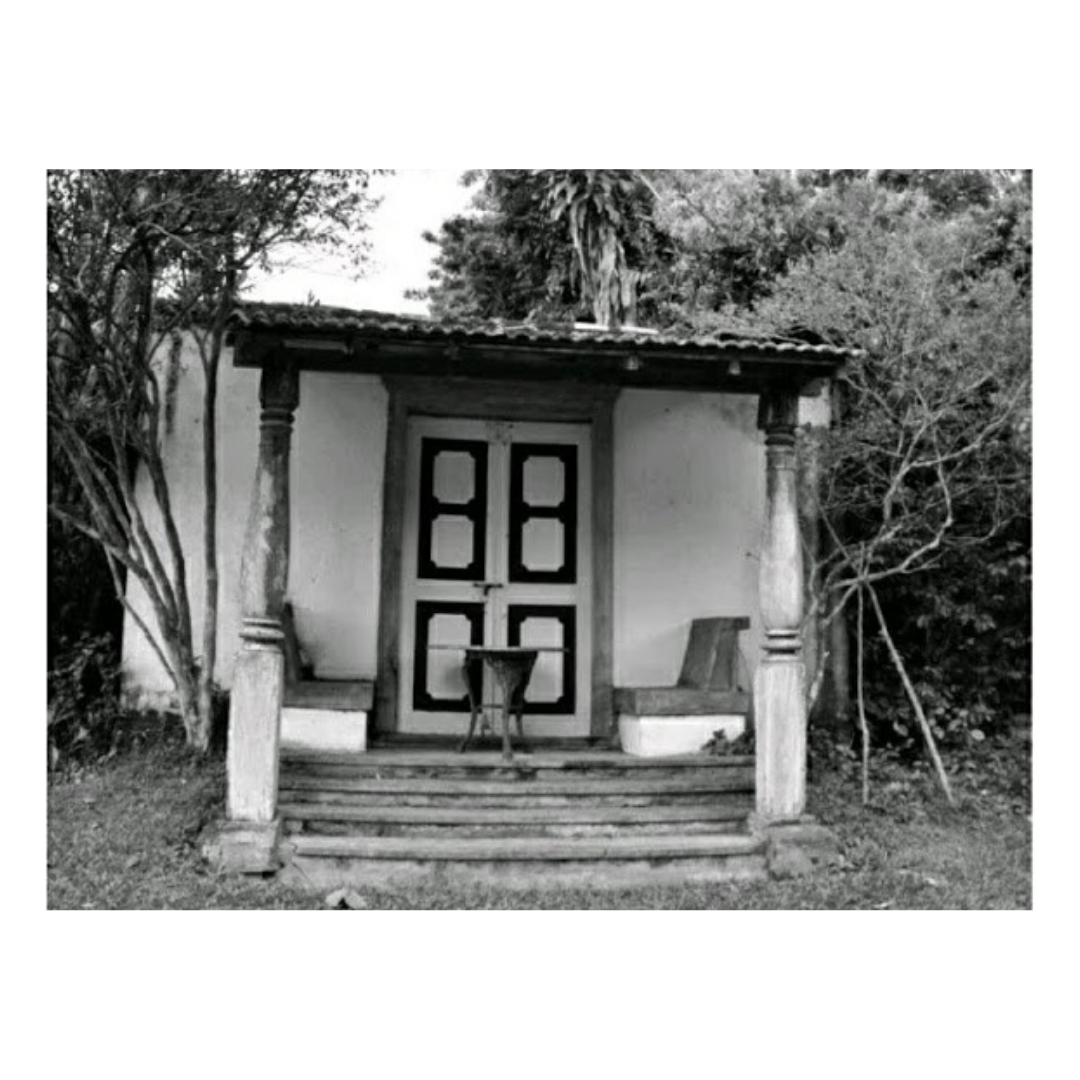

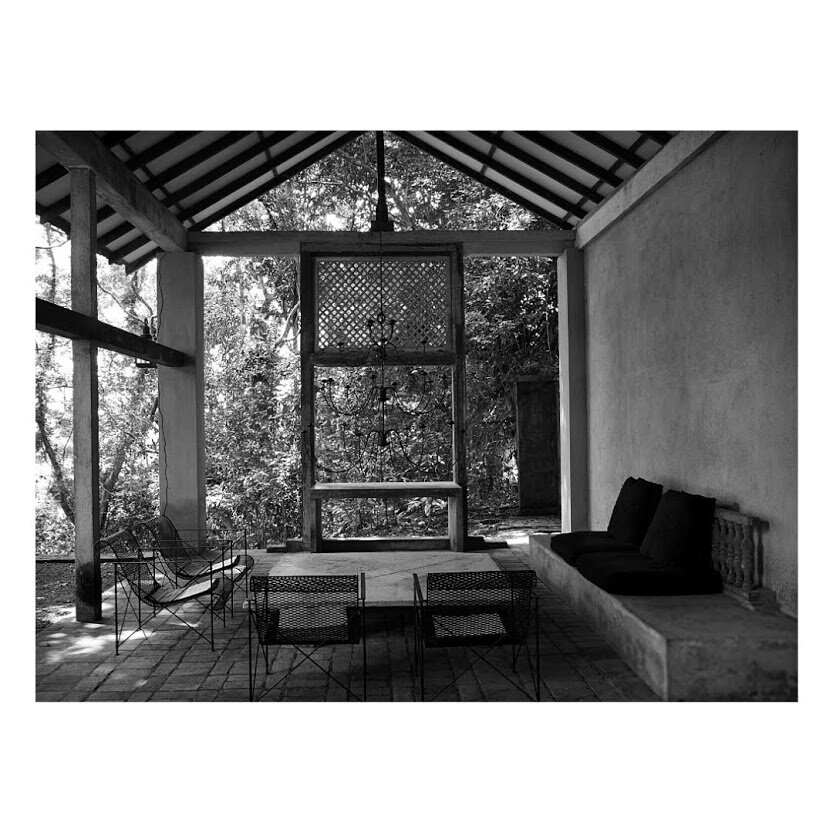

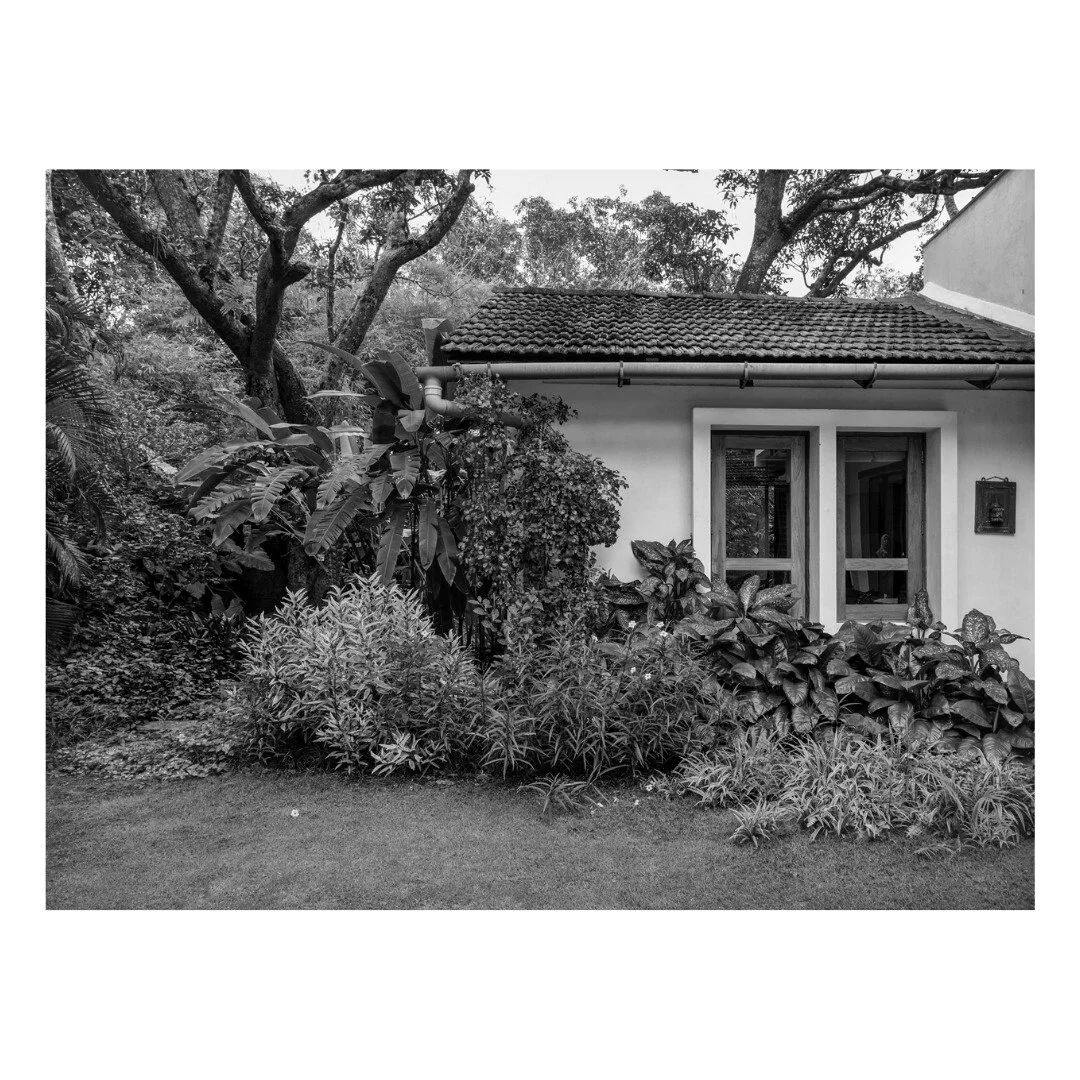

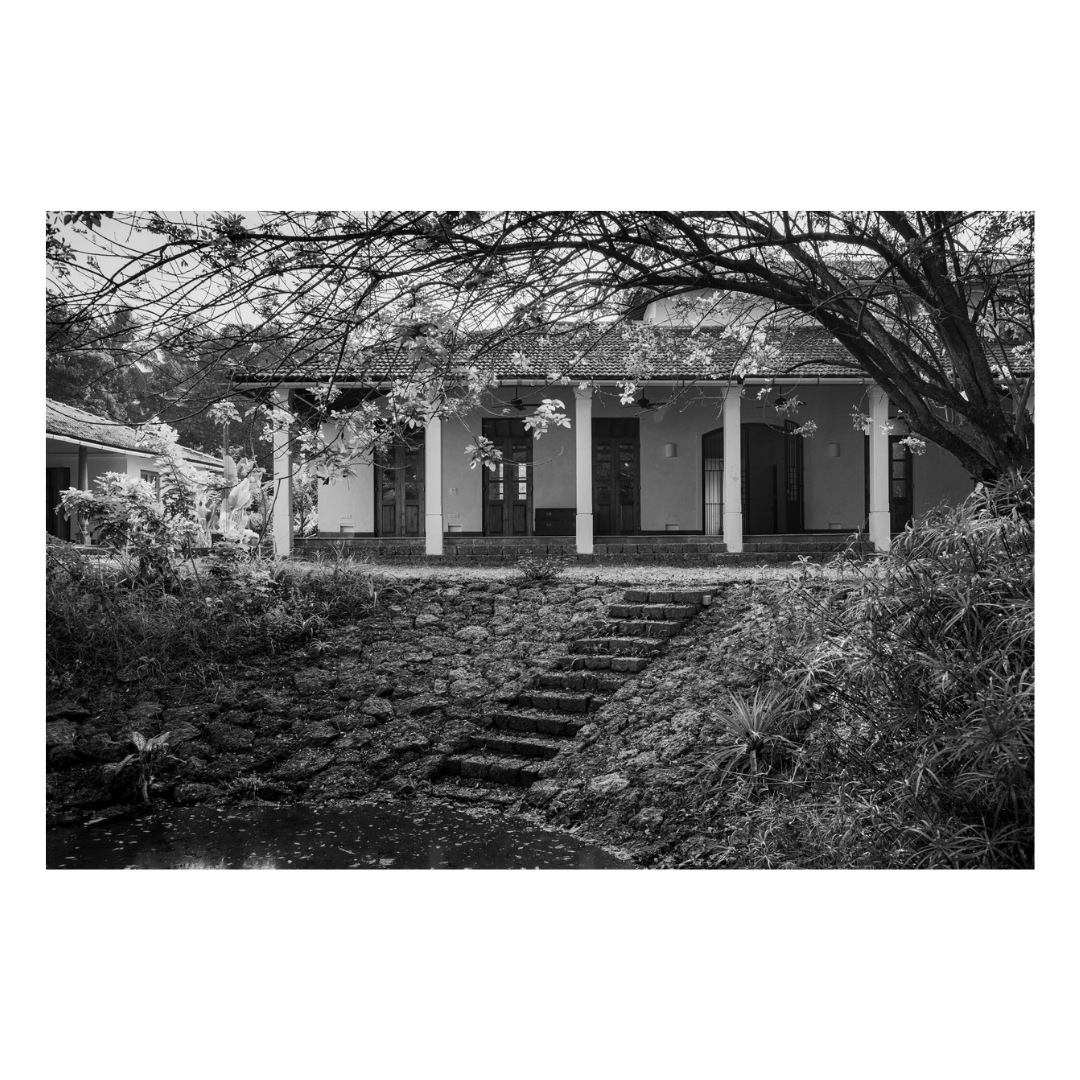

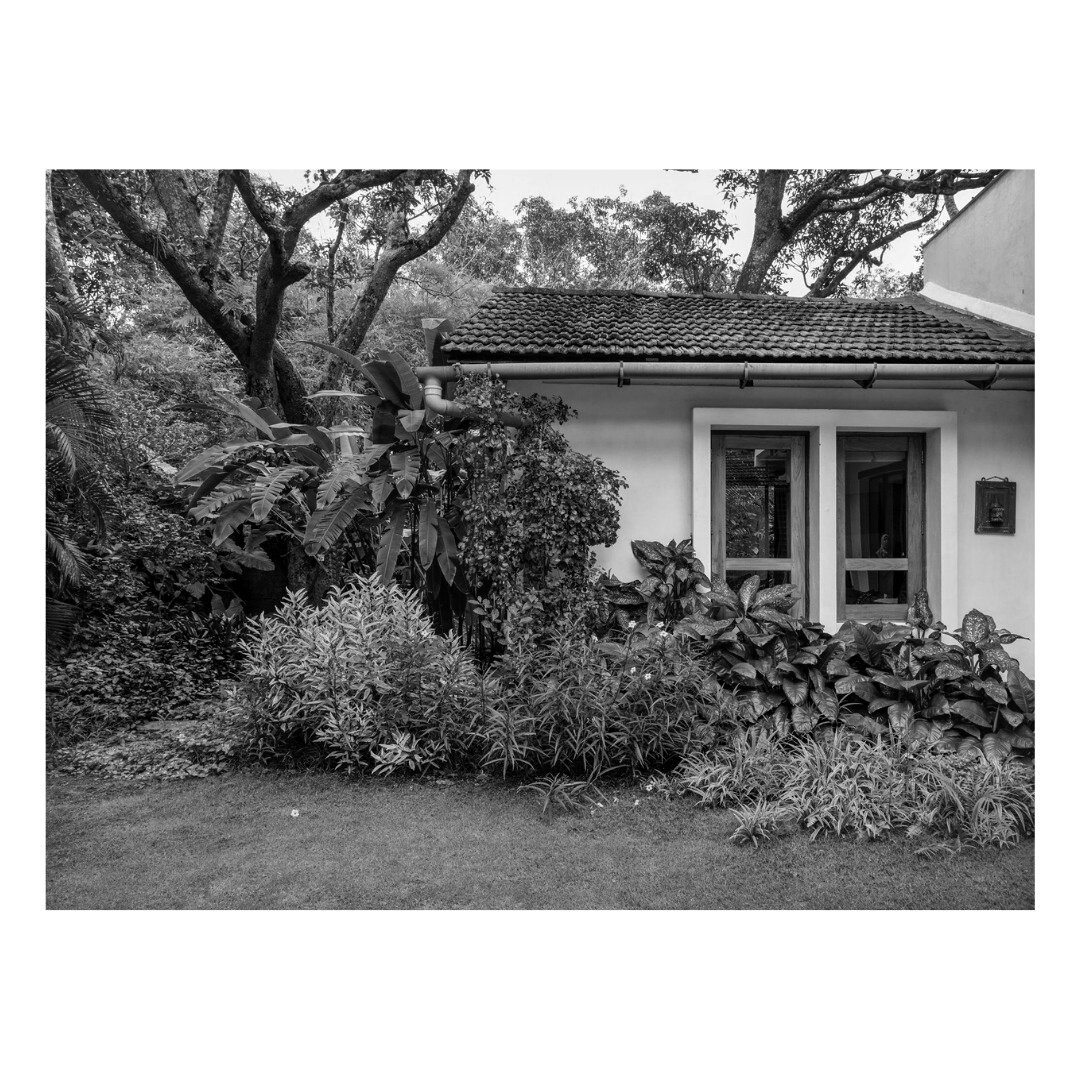

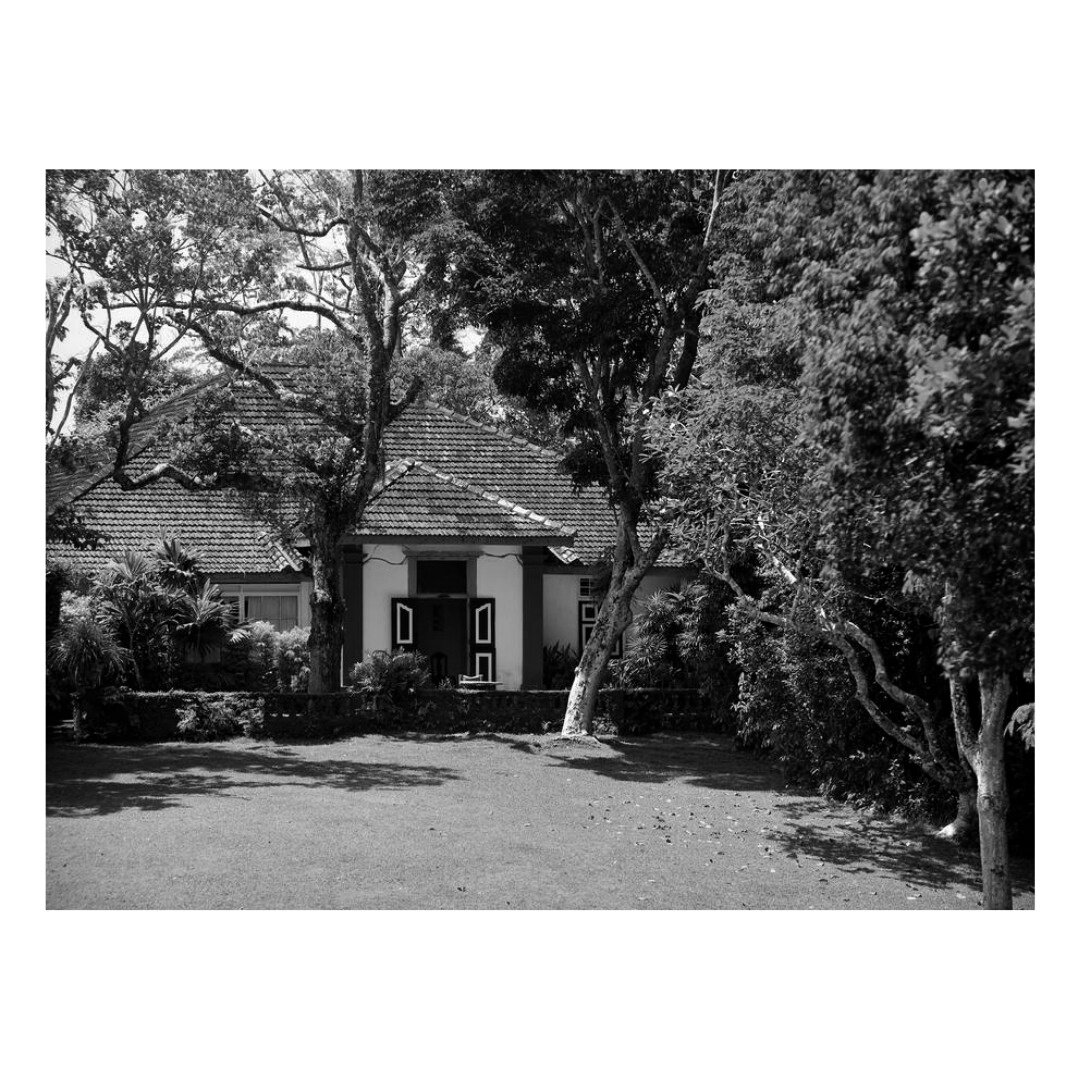

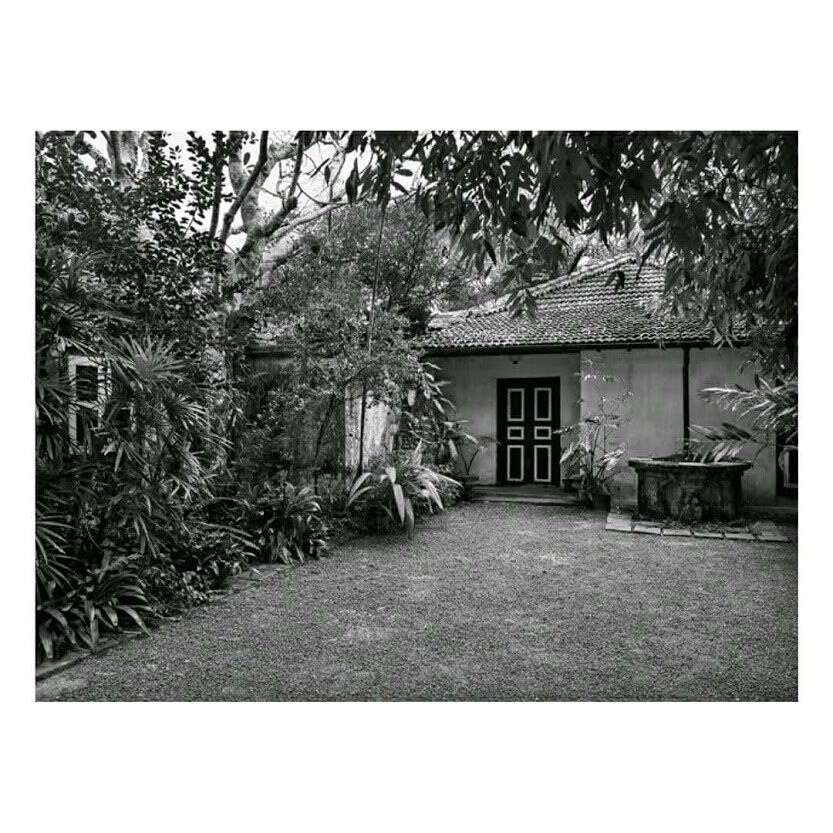

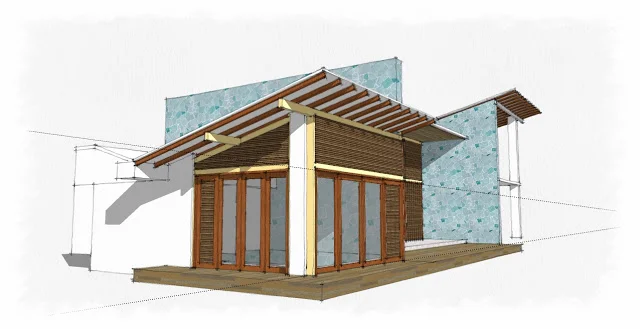

Celebrating Navovado, our design-build vacation house in the Goan countryside through a gallery of photographs of the courtyard house. Earlier this year, Navovado won the prestigious Platinum Certification from the Indian Green Building Council. Navovado harvests all of its roof rainwater and recharges the water well on site. The use of low-flow water fixtures further improves water efficiency. Focus on use of insulation on the roof, double-glazed glass, lowenergy use appliances, LED lighting and 100% hot water from Solar power makes this home extremely energy efficient. The structure is constructed using locally manufactured materials and materials with a high recycled content such as Laterite stone, Matti wood, Fly-ash brick and Slag cement. The garden is planted using native local species to reduce water use for irrigation. Finally, large openings allow for maximum daylighting and cross-ventilation, reducing the energy use for lighting and cooling.

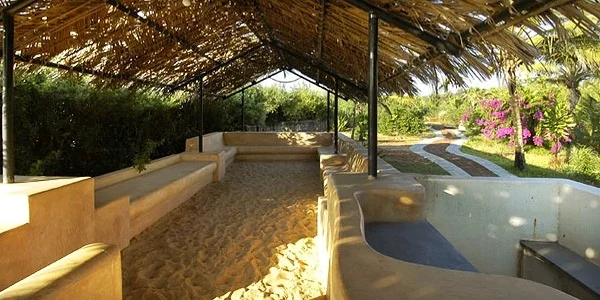

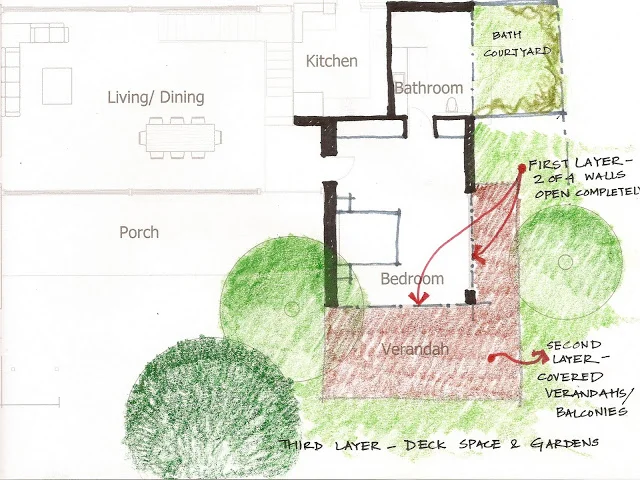

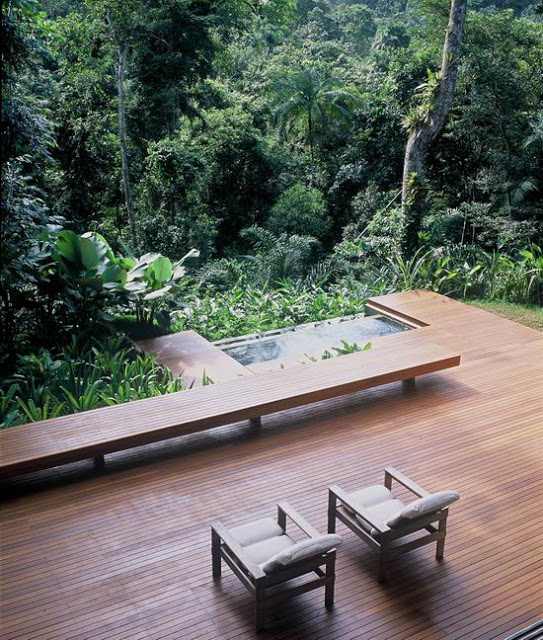

The heart of the home lies in the large central courtyard that is an extension of the kitchen, living and dining space. The courtyard houses the swimming pool and provides a green private space to be enjoyed by all the residents of the house. The courtyard morphs in its use depending on the time of day and occasion. The guest bedrooms on the ground floor are designed as pavilions on either side of the courtyard, while the first-floor bedrooms have a large terrace overlooking the courtyard that connects the two levels.

Find Navovado featured in detail on our Instagram page here.